In the aftermath of the Great War memorials to those who died were erected in almost every town and village in the United Kingdom. Repatriation of the bodies of those who fell abroad had not been permitted and some were sadly lost. Organised at the time by local groups war memorials take many forms and each one is unique. They acted as a focus of public commemoration, personal remembrance, a means of accepting loss and of saying goodbye to a loved one. The unveiling of war memorials, in a small way, filled the gap left by the bereaved families’ inability to have a traditional funeral.

At the start of the new academic year in 1914 the Vice Chancellor, Professor Frederick Ernest Weiss movingly wrote:

“We are assembling under very exceptional and totally unexpected circumstances. Like a dark cloud the consciousness of the Great War, in which we are engaged, hangs over us, and we shall sorely miss the companionship of many students and some members of the Staff who are serving their country at the front or preparing themselves in various camps to step into the firing line. All of these have our sincerest wishes for their welfare and for their safe return. That the thought of their self sacrifice and their devotion to their duty, will be with us throughout the session, who can doubt.”

Unforeseen by many, the war lasted far longer than just one academic session. The names of 626 men and one woman are recorded across the University’s war memorials, of which there are four to multiple people and two to individuals.

The Tech Memorial

In the 1910s The Manchester School of Technology had an annual intake of 5-6,000 day release and evening students, plus 200 degree students in it’s capacity as the Faculty of Technology of Manchester University. It was known at the time as ‘The Tech’. Many will have known it as UMIST (University of Manchester Institute for Technology) before it merged with Manchester University in 2004.

This memorial is located on B Floor of the Sackville Building. Unveiled on 11th November 1921 at 11am, the Manchester Evening News reported:

Women could not restrain the tears, and men clung to the nearest chair to steady themselves as the buglers sounded the “Last Post”.

The thrilling notes died away and calm fell upon the whole building, broken only by a sobbing mother whose little sheaf of white chrysanthemums told its own simple tale and was to be laid at the foot of the newly unveiled memorial to the students and members of the College who were killed or injured in the war.

The buglers sharply broke the reverie of the great audience that filled the Statuary Hall, where the pieces of a wrecked Zeppelin and a full sized model of a British aeroplane served as additional painful reminders of the strife of the past.

Mr. J.H. Reynolds, a past principal of the College and Dean of the Faculty of Technology, unveiled the memorial and said that he was sure it would remain “a valued possession of the institution and an inspiration to the youth of the future to make the great sacrifice in defence of true liberty”.

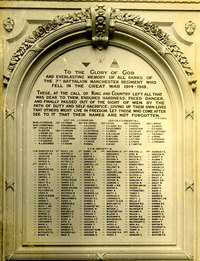

Consisting of three wooden panels with ornate gold lettering it was designed by Henry Cadness, Design Master and Principal of Manchester School of Art. A local craftsman and teacher of wood carving at the School of Art, James Lenegan, made the memorial. The inscriptions read “To the Glory and Honour of the Members of this College who gave their lives in the Great War 1914-1918. Honour the Brave. Their Names Shall Endure.”

There are 194 names listed alphabetically on it, except for some at the end which are presumed to be late additions.

The Hulme Hall Memorial

For many students, then and now, a stint in Halls of Residence is one of the most significant aspects of their time at University. The bond formed to their Hall and the friends they make there often being ones for life. It was estimated after the war that 230 current and former residents and staff of Hulme Hall had served in the armed forces, approximately 50% of students who had passed through the Hall it since it’s foundation in 1877. Of those 34 died and are remembered on this memorial “To the glory of God and in memory of the members of this hall who gave their lives in the Great War“.

A service was held in March 1917 to remember those from the Hall who had been killed and a project was in hand to raise money for a permanent memorial. By 1923 sufficient funds had been secured and the tablet of oak and bronze located on the west end wall of the chapel, was unveiled on Friday 26th October 1923. In the presence of relatives, the Bishop of Manchester dedicated the memorial and reflected:

“The losses of the War have fallen most heavily on Societies like this. The young had necessarily been the chief victims. They had offered their all to defeat a movement towards a World Empire of Might and such a cause was “God’s Cause”.

The memorial has since moved to a new Hall chapel built in the 1960s.

The Quad Memorial

It was designed by Prof. A.C. Dickie, Chair of Architecture at the University and sculpted by the firm Earp, Hobbs and Miller. A quote from them in the University archive estimated the cost at between £800 and £850 pounds, which would be approximately £42,000 today. Placed in a prominent position under a clock on the side of the John Owen’s Building, in the main quadrangle, it consists of a bronze tablet and is 13ft wide and over 4ft high. The central panel carries the University coat of arms flanked by child figures and an inscription (see picture at top of page).

511 names are recorded here. In contrast to the other memorials this one does not list the names alphabetically. The ordering follows military precedence. The Navy as the Senior Service is listed first, then the Army with the artillery, cavalry/tank, engineers, and then infantry regiments oldest to newest. Men are then listed by rank under their regiment, and within that alphabetically. The Officer Training Corps had a strong influence on how the names were listed. It gives some sense of order to the loss, but does make a distinction between the men that is not as prominent, or present, on the other memorials.

Unveiled on Saturday 29th November 1924 the proceedings started when the Officer Training Corps guard of honour formed up at 10.30am in the quad for an inspection by the University Chancellor, the Earl of Crawford and Balcarres, who had himself served in the war in the Royal Army Medical Corps. University members, including the Vice Chancellor Sir Henry Miers, former Chancellor Weiss, relatives and the Officers Training Corps then entered Whitworth Hall in a procession for an 11am service. Canon Scott conducted the service. He and Professor Peake (Professor of Biblical Criticism), read passages of scripture. The University Choral Society sang sentences, there were hymns, the Lords Prayer was spoken and the Chancellor gave an address. The Dead March by Handel was played, everyone left the hall and crossed the quad to the memorial. The Chancellor pulled a cord that released the flag covering the memorial, read aloud the inscription, and Canon Scott dedicated the tablets. Buglers of the Manchester Regiment sounded The “Last post” and “Reveille”.

By the time of the unveiling, those that had returned from the war to complete or start their studies, had graduated.

Manchester University Engineering Department War Memorial

We know very little about this memorial. A colleague, who has access to parts of buildings most of us will never be permitted to go, told me about a what he thought was a memorial in ‘storage’ on a service corridor. When he went to check if it was still there it had gone. It turned up a couple of years later on a wall in the basement of the George Begg Building, near some engineering labs, in a small display area. A far simpler memorial than the others, the lettering is not so well defined. It is metal, quite rough to the touch, and appears to have undergone some restoration.

Dalton Hall

Founded in 1876, Dalton Hall is one of the oldest halls outside Oxford and Cambridge. It has no memorial, but this is perhaps not unexpected as it was administered by the Society of Friends, a Quaker organization whose members were usually conscientious objectors to war. Indeed 3 men from the Hall were imprisoned in Britain during the Great War for holding this view and the principal John Graham was a frequent writer of letters to the Manchester Guardian which led to controversy when some people declared his views to be anti-british and pro-german.

The Daltonian hall magazine lists 26 men who died, 20 of whom are on University memorials. In addition a number died of influenza post war, one of these served in the Belgian Army and is on the Quad Memorial. A dozen others served in the forces and survived, two were prisoners of war.

St Anslem Hall – Thomas Robinson

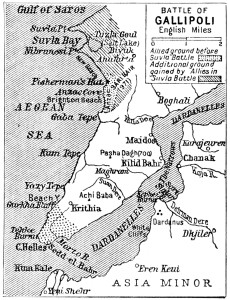

St. Anselm, known affectionately as ‘Slems’, is a Hall of Residence in the Victoria Park area of Manchester, founded in 1907 by the Church of England. There is a small plaque in the chapel to those who have “died in the service of mankind”, but it is not clear when or why that was erected. A painting in the chapel of an English knight kneeling to pray carries a dedication to Thomas Robinson. He came to the University in 1913 as a student of Arts and died during the Gallipoli campaign serving with the Royal Naval Division.

Schuster Building – Henry Moseley

On 25th November 1921 a tablet in memory of Henry Moseley was unveiled by his mother at a ceremony in the physics building, which was at the time part of the buildings around the quad. It is now located at the back of a lecture theatre in the Schuster Building.

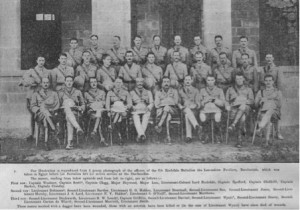

7th Manchester Regiment

Although not a a University memorial, there are a number of strong connections between the University and the unit commemorated on this memorial in Whitworth Park.

Conclusion

Memorials to those who perished during the Great War still see a yearly observance of silence and the laying of poppies and wreaths on Remembrance Sunday and Armistice Day by the modern day communities who live and work near them. Relatives still visit all year round to pay their respects to their ancestors. The University’s memorials are no exception.

Professor Wilkinson, former lecturer in Military History at the University, in 1918, during his Founders Day address, said of those the University lost in the war:

“All of them gave all that they were and all that they might have been.”

Acknowledgments

James Hern (Hulme Hall memorial), Neil Shuttleworth and The Late Professor Hankins (The Tech memorial), Dr. Timothy Stibbs, Principal of Dalton-Ellis Hall, & Laura Turner, Warden of St Anselm Hall and Canterbury Court.