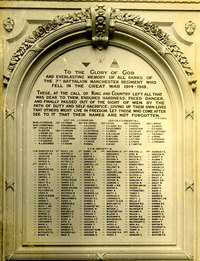

“They did not even have a filing cabinet,” said Prof. Harold Hankins, CBE, FEng when he began researching the history of the Manchester and Salford Universities Officers Training Corps (MUOTC). Sometime later he had produced its 296-page definitive history which spanned the years 1898 to 2002, and for its Great War chapter incorporated much of his earlier monograph: The Manchester University Officers Training Corps – The Great War 1914-1919. He could not find a single Roll of Honour for the OTC, and so began to rectify this omission. The latter is dedicated to the 314 members of the MUOTC “who laid down their lives in the Great War 1914-1919 defending the freedoms we take for granted today.”

Poignantly he ends his preface by citing a survivor: 2nd Lieutenant J D Cockcroft [born 1897; MUOTC, Oct 1914; enlisted Nov 1915, Royal Field Artillery 1915-1918; B Sc Tech, 1920; M Sc Tech, 1921] who with Ernest Walton split the atom in 1932, and received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1956. John died in 1967 aged 70.

Such were the opportunities available to those members of the MUOTC who had survived the War and who possessed the talent and inspiration to succeed. Sadly, such opportunities were denied to their 314 comrades in death, and we can never know what they might have achieved had they lived.

After graduating with a first in 1955, Harold worked in industry, then returned to lecture at ‘the Tech’, as the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (UMIST) was colloquially known. There he often passed the Great War Memorial to nearly 200 men. On retirement from UMIST in 1995 as its Principal he started to research in earnest the lives of those commemorated on the Memorial, an enormous project as he planned to visit their final resting places. His regular battlefield companion and tutor was Michael Seward, who along with his late wife, Harold and his wife, Kathleen, made many visits to the cemeteries and battlefields of northern France and Belgium. (Michael’s interest was in members of his old school, Uppingham.) They found that the only military grave in the communal cemetery of Briastre, a small village east of Cambrai, was that of Lieutenant A J H R Widdowson. The second MUOTC to fall, he was killed on 25 August 1914 after the retreat from Mons. Mr. Seward is full of praise for Harold’s work which is remarkable for the amount of detail, and he reckons that Harold’s son Nick deserves much credit too.

As a former Tech student I collaborated with Harold in his project, and was later described as ‘a colleague’. Had Harold not started down this path I fear few would have trod it. Thanks to our collective efforts we have ensured that the names of the fallen are not forgotten. For instance, Henry M Weyman once had no headstone in Philips Park, Manchester; now he has one. Similarly Harold Beard, who was a given a full military funeral before being buried in the family grave, was initially not recognised on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website. Due to our efforts he is now.

I sense that all the men were real to Harold and like any good teacher knew their background intimately. On one occasion after he had given a talk to the OTC he was asked by the officer who had commissioned him to give the talk “where are your notes or the hand-outs?” He replied that when he was a lecturer at the Tech that was the norm, otherwise students thought that you did not know your subject.

Although Harold was of the belief that the work of the 196 Tech men could not be published until all had been identified, it is with a few uncertainties which are difficult to resolve that the work was published. It was dedicated to him and the men who fell. Initially Harold had paper copies of the War Office documents listing those who died in the Great War. With the advent in 1998 of the CD-ROM “Soldiers/Officers who died in the Great War 1914-1919” by Naval and Military Press, and the incredible Commonwealth War Graves Commission website the searching process was speeded up.

When Harold died in 2009 the Independent’s obituary described him as the “ultimate Manchester Tech man” because he had been a student and risen to become its Principal. He was always at pains to point out that our work will leave its mark by remembering the Tech men who gave their lives a century ago. Now Harold, the “ultimate Tech man,” has left his mark with three publications which details their educational, professional and military lives. You would need a filing cabinet to hold these records, but thanks to his labour of love he has brought their stories to life. We salute his enthusiasm and dedication in helping us to remember them.

Further reading:

A History of the Manchester and Salford Universities OTC 1898-2002

The Manchester University Officers Training Corps – The Great War 1914-1919